|

| Arthur Edward Waite |

WAITE What is Alchemy ?

WHAT IS ALCHEMY ?

By

Arthur Edward Waite

Published in "The Unknown World", from August to December 1894

and in April, 1895

There are certain writers at the present day, and there are certain students of the subject, perhaps too wise to write, who would readily, and do, affirm that any answer to the question which heads this paper will involve, if adequate, an answer to those other and seemingly harder problems- What is Mysticism? What is the Transcendental Philosophy? What is Magic? What Occult Science? What the Hermetic Wisdom? For they would affirm that Alchemy includes all these, and so far at least as the world which lies west of Alexandria is concerned, it is the head and crown of all. Now in this statement the central canon of a whole body of esoteric criticism is contained in the proverbial nut-shell, and this criticism is in itself so important, and embodies so astounding an interpretation of a literature which is so mysterious, that in any consideration of Hermetic literature it must be reckoned with from the beginning; otherwise the mystic student will at a later period be forced to go over his ground step by step for a second time, and that even from the starting point. It is proposed in the following papers to answer definitely by the help of the evidence which is to be found in the writings of the Alchemists the question as to what Alchemy actually was and is. As in other subjects, so also in this, The Unknown World proposes to itself an investigation which has not been attempted hitherto along similar lines, since at the present day, even among the students of the occult, there are few persons sufficiently instructed for an inquiry which is not only most laborious in itself but is rendered additionally difficult from the necessity of expressing its result in a manner at once readable and intelligible to the reader who is not a specialist. In a word, it is required to popularise the conclusions arrived at by a singularly abstruse erudition. This is difficult- as will be admitted- but it can be done, and it is guaranteed to the readers of these papers that they need know nothing of the matter beforehand. After the little course has been completed it is believed that they will have acquired much, in fact, nothing short of a solution of the whole problem.

In the first place, let any unversed person cast about within himself, or within the miscellaneous circle of his non-mystical acquaintance, and decide what he and they do actually at the present moment understand by Alchemy. It is quite certain that the answer will be fairly representative of all general opinion, and in effect it will be somewhat as follows: "Alchemy is a pretended science or art by which the metals ignorantly called base, such as lead and iron were supposed to be, but were never really, transmuted into the other metals as ignorantly called perfect, namely, gold and silver. The ignis fatuus of Alchemy was pursued by many persons- indeed, by thousands- in the past, and though they did not succeed in making gold or silver, they yet chanced in their investigations upon so many useful facts that they actually laid the foundations of chemistry as it is. For this reason it would perhaps be unjust to dishonour them; no doubt many of them were rank imposters, but not all; some were the chemists of their period." It follows from this answer that this guesswork and these gropings of the past can have nothing but a historical interest in the present advanced state of chemical knowledge. It is, of course, absurd to have recourse to an exploded scientific literature for reliable information of any kind. Goldsmith and Pinnock in history, Joyce and Mangnall in general elementary science, would be preferable to the Alchemists in chemistry. If Alchemy be really included as a branch of occult wisdom, then so much the worse for the wisdom- ex uno disce omnia. The question what is Alchemy is then easily answered from this standpoint- it is the dry bones of chemistry, as the Occult Sciences in general are the debris of ancient knowledge, and the dust from the ancient sanctuaries of long vanished religions- at which point these papers and The Unknown World itself; would perforce come to a conclusion.

There is, however, another point of view, and that is the standpoint of the occultist. It will be pardonable perhaps to state it in an occult magazine. Now, what does the student of the Occult Sciences understand by Alchemy? Of two things, one, and let the second be reserved for the moment in the interests of that simplicity whicht he Alchemists themselves say is the seal of Nature and art- sigillum Natura et artis simplicitas. He understands the law of evolution applied by science to the development from a latent into an active condition of the essential properties of metallic and other substances. He does not understand that lead as lead or that iron as iron can be transmuted into gold or silver. He affirms that there is a common basis of all the metals, that they are not really elements, and that they are resolvable. In this case, once their component parts are known the metals will be capable of manufacture, though whether by a prohibitively expensive process is another issue. Now, beyond contradiction this is a tolerable standpoint from the standpoint of modern science itself. Chemistry is still occasionally discovering new elements, and it is occasionally resolving old and so-called elements, and indeed, a common basis of all the elements is a thing that has been talked of by, men whom no one would suspect of being Mystics, either in matters of physics or philosophy.

There is, however, one obviously vulnerable point about this defensive explanation of Alchemy. It is open to the test question: Can the occultist who propounds it resolve the metallic elements, and can he make gold? If not, he is talking hypothesis alone, tolerable perhaps in the bare field of speculation, but to little real purpose until it can be proved by the event. Now, The Unknown World has not been established to descant upon mere speculations or to expound dreams to its readers. It will not ignore speculation, but its chief object is to impart solid knowledge. Above all it desires to deal candidly on every subject. There are occultists at the present day who claim to have made gold. There are other occultists who claim to be in communication with those who possess the secret. About neither classis it necessary to say anything at present; claims which it is impossible to verify may be none the less good claims, but they are necessarily outside evidence. So far as can be known the occultist does not manufacture gold. At the same time his defence of Alchemy is not founded on merely hypothetical considerations. It rests on a solid basis, and that is alchemical literature and history. Here his position, whether unassailable or not, cannot be impugned by his opponents, and this for the plain reason that, so far as it is possible to gather, few of them know anything of the history and all are ignorant of the literature. He has therefore that right to speak which is given only by knowledge, and he has the further presumption in his favour that as regards archaic documents those who can give the sense can most likely explain the meaning. To put the matter as briefly as possible, the occultist finds in the great text- books of Alchemy an instruction which is virtually as old as Alchemy, namely, that the metals are composite substances. This instruction is accompanied by a claim which is, in effect, that the Alchemists had through their investigations become acquainted with a process which demonstrated by their resolution the alleged fact that metals are not of a simple nature. Furthermore, the claim itself is found side by side with a process which pretends to be practical, which is given furthermore in a detailed manner, for accomplishing the disintegration in question. Thus it would seem that in a supposed twilight of chemical science, in an apparently inchoate condition of physics, there were men in possession of a power with which the most advanced applied knowledge of this nineteenth century is not as yet equipped. This is the first point in the defence of Alchemy which will be raised by the informed occultist. But, in the second place, there is another instruction to be found in these old text-books, and that is the instruction of development- the absolute recognition that in all natural substances there exist potentialities which can be developed by the art of a skilled physicist, and the method of this education is pretended to be imparted by the textbooks, so that here again we find a doctrine, and connected with that doctrine a formal practice, which is not only in advance of the supposed science of the period but is actually a governing doctrine and a palmary source of illumination at the present day. Thirdly, the testimony of Alchemical literature to these two instructions, and to the processes which applied them, is not a casual, isolated, or conflicting testimony, nor again is it read into the literature by a specious method of interpretation; it is upon the face of the whole literature; amidst an extraordinary variety of formal difference, and amidst protean disguises of terminology, there is found the same radical teaching everywhere. In whatsoever age or country, the adepts on all ultimate matters never disagree- a point upon which they themselves frequently insist, regarding their singular unanimity as a proof of the truth of their art. So much as regards the literature of Alchemy, and from this the occultist would appeal to the history of the secret sciences for convincing evidence that, if evidence be anything, transmutations have taken place. He would appeal to the case of Glauber, to the case of Van Helmont, to the case of Lascaris and his disciples, to that also of Michael Sendivogius, and if his instances were limited to these it is not from a paucity of further testimony, but because the earlier examples, such as Raymond Lully, Nicholas Flamel, Bernard Trevisan, and Denis Zachaire, will be regarded as of less force and value in view of their more remote epoch. Having established these points, the occultist will proceed to affirm that they afford a sufficient warrant for the serious investigation of Alchemical literature with the object of discovering the actual process followed by the old adepts for the attainment of their singular purpose. He will frankly confess that this process still remains to be understood, because it has been veiled by its professors, wrapped up in strange symbols, and disguised by a terminology which offers peculiar difficulties. Why it has been thus wilfully entangled, why it was considered advisable to make it caviare to the multitude, and what purpose was served by the writing of an interminable series of books seemingly beyond comprehension, are points which must be held over for consideration in their proper place later on. Those who, for what reason so ever, have determined to study occultism, must be content to take its branches as they are, namely, as sciences that have always been kept secret. It follows from what has been advanced that the occultist should not be asked, as a test question, whether he can make gold, but whether he is warranted in taking the Alchemical claim seriously, in other words, whether the literature of Alchemy, amidst all its mystery, does offer some hope for its unravelment, and if on the authority of his acquaintance therewith he can, as he does, assuredly answer yes, then he is entitled to a hearing.

Now, the issue which has been dealt with hitherto in respect of Alchemy is one that is exceedingly simple. Assuming there is strong presumptive evidence that the adepts could and did manufacture the precious metals, and that they enclosed the secret of their method in a symbolic literature, it is a mere question of getting to understand the symbolism, about which it will be well to remember the axiom of Edgar Allan Poe, himself a literary Mystic, that no cryptogram invented by human ingenuity is incapable of solution by the application of human ingenuity. But there is another issue which is not by any means so simple, the existence of which was hinted at in the beginning of the present paper, and this is indeed the subject of the present inquiry. To put it in a manner so elementary as to be almost crude in presentation, there is another school of occult students who believe themselves to have discovered in Alchemy a philosophical experiment which far transcends any physical achievement. At least in its later stages and developments this school by no means denies the fact that the manufacture of material gold and silver was an object with many Alchemists, or that such a work is possible and has taken place. But they affirm that the process in metals is subordinate, and, in a sense, almost accidental, that essentially the Hermetic experiment was a spiritual experiment, and the achievement a spiritual achievement. For the evidence of this interpretation they tax the entire literature, and their citations carry with them not infrequently an extraordinary, and sometimes an irresistible, force. The exaltation of the base nature in man, by the development of his latent powers; the purification, conversion, and transmutation of man; the achievement of a hypostatic union of man with God; in a word, the accomplishment of what has been elsewhere in this magazine explained to be the true end of universal Mysticism; not only was all this the concealed aim of Alchemy, but the process by which this union was effected, veiled under the symbolism of chemistry, is the process with which the literature is concerned, which process also is alone described by all veritable adepts. The man who by proper study and contemplation, united to an appropriate interior attitude, with a corresponding conduct on the part of the exterior personality, attains a correct interpretation of Hermetic symbolism, will, in doing so, be put in possession of the secret of divine reunion, and will, so far as the requisite knowledge is concerned, be in a position to encompass the great work of the Mystics. From the standpoint of this criticism the power which operates in the transmutation of metals alchemically is, in the main, a psychic power. That is to say, a man who has passed a certain point in his spiritual development, after the mode of the Mystics, has a knowledge and control of physical forces which are not in the possession of ordinary humanity. As to this last point there is nothing inherently unreasonable in the conception that an advancing evolution, whether in the individual or the race, will give a far larger familiarity with the mysteries and the laws of the universe. On the other hand, the grand central doctrine and the supreme hope of Mysticism, that it is possible for "the divine in man" to be borne back consciously to "the divine in the universe," which was the last aspiration of Plotinus, does not need insistence in this place. There is no other object, as there is no other hope, in the whole of Transcendental Philosophy, while the development of this principle and the ministration to this desire are the chief purpose of The Unknown World.

It is obvious that Alchemy, understood in this larger sense, is mystically of far higher import than a mere secret science of the manufacture of precious metals. And this being incontestable, it becomes a matter for serious inquiry which of these occult methods of interpretation is to be regarded as true. A first step towards the settlement of this problem will be a concise history of the spiritual theory. Despite his colossal doctrine of Hermetic development, nothing to the present purpose, or nothing that is sufficiently demonstrable to be of real moment, is found in the works of Paracelsus. The first traces are supposed to be imbedded in the writings of Jacob Bohme and about the same time Louis Claude de Saint Martin, the French illumine, is discovered occasionally describing spiritual truths in the language of physical chemistry. These, however, are at best but traces, very meagre and very indefinite. It was not till the year 1850, and in England, that the interpretation was definitely promulgated. In that year there appeared a work entitled A Suggestive Inquiry Into The Hermetic Mystery And Alchemy, Being An Attempt To Discover The Ancient Experiment Of Nature. This was a large octavo of considerable bulk; it was the production of an anonymous writer, who is now known to be a woman, whose name also is now well known, at least in certain circles, though it would be bad taste to mention it. For the peculiar character of its research, for the quaint individuality of its style, for the extraordinary wealth of suggestion which more than justifies its title, independently of the new departure which it makes in the interpretation of Hermetic symbolism, truly, this book was remarkable.

Eliphas Levi affirms that all religions have issued from the Kabbalah and return into it; and if the term be intended to include the whole body of esoteric knowledge, no advanced occultist will be likely to dispute the statement. So far as books are concerned, it may, in like manner, be affirmed that all modern mystical literature is referable ultimately to two chief sources: on the one hand, to the wonderful books on Magic which were written by Eliphas Levi himself, and of which but a faint conception is given in the sole existing translation; and, on the other, to the "Suggestive Inquiry Concerning the Hermetic Mystery," that singular work to which reference was made last month as containing the first promulgation of the spiritual theory of Alchemy. This seems at first sight an extreme statement, and it is scarcely designed to maintain, that, for example, the Oriental doctrine of Karma is traceable in the writings of the French initiate who adopted the Jewish pseudonym of Eliphas Levi Zahed, nor that the "recovered Gnosis" of the "New Gospel of Interpretation" is borrowed from the Suggestive Inquiry. But these are the two chief sources of inspiration, in the sense that they have prompted research, and that it is not necessary to go outside them to understand how it is that we have come later on to have Theosophy, Christo-Theosophy, the New Kabbalism of Dr. Wynn Westcott, and the illuminations of Mrs. Kingsford. Everywhere in Isis Unveiled the influence of Eliphas Levi is distinctly traceable; everywhere in the Recovered Gnosis there is the suggestion of the Inquiry. Even the Rosicrucianism of the late Mr. Hargrave Jennings, so far as it is anything but confusion, is referable to the last mentioned work. It is doubtful if Eliphas Levi did not himself owe something to its potent influence, for his course of transcendental philosophy post dates the treatise on the Hermetic Mystery by something like ten years, and he is supposed to have accomplished wide reading in occult literature, and would seem to have known English. As it is to the magical hypotheses of the Frenchman that we are indebted for the doctrines of the astral light and for the explanations of spiritualistic phenomena which are current in theosophical circles, to name only two typical instances, so it is of the English lady that we have derived the transcendental views of alchemy, also every where now current, and not among Theosophists only. At the same time, it is theosophical literature chiefly which has multiplied the knowledge concerning it, though it does not always indicate familiarity with the source of the views. It is also to Theosophy that we owe the attempt to effect a compromise between the two schools of alchemical criticism mentioned last month, by the supposition that there were several planes of operation in alchemy, of which the metallic region was one.

Later speculations have, however, for the most part, added little to the theory as it originally stood, and the Suggetive Inquiry is in this respect still thoroughly representative.

To understand what is advanced in this work is to understand the whole theory, but to an unprepared student its terminology would perhaps offer certain difficulties, and therefore in attempting a brief synopsis, it will be well to present it in the simplest possible manner.

The sole connection, according to the Suggestive Inquiry, which subsists between Alchemy and the modern art of Chemistry is one of terms only. Alchemy is not an art of metals, but it is the Art of Life; the chemical phraseology is a veil only, and a veil which was made use of not with any arbitrary and insufficient desire to conceal for the sake of concealment, or even to ensure safety during ages of intolerance, but because the alchemical experiment is attended with great danger to man in his normal state. What, however the adepts in their writings have most strenuously sought to conceal is the nature of the Hermetic Vessel, which they admit to be a divine secret, and yet no one can intelligently study these writings without being convinced that the vessel is Man himself. Geber, for example, to quote only one among many, declares that the universal orb of the earth contains not so great mysteries and excellencies as Man re-formed by God into His image, and he that desires the primacy amongst the students of Nature will no where find a greater or better subject wherein to obtain his desire than in himself, who is able to draw to himself what the alchemists call the Central Salt of Nature, who also in his regenerated wisdom possesses all things, and can unlock the most hidden mysteries. Man is, in fact, with all adepts, the one subject that contains all, and he only need be investigated for the discovery of all. Man is the true laboratory of the Hermetic Art, his life is the subject, the grand distillery, the thing distilling and the thing distilled, and self-knowledge is at the root of all alchemical tradition. To discover then the secret of Alchemy the student must look within and scrutinize true psychical experience, having regard especially to the germ of a higher faculty not commonly exercised but of which he is still in possession, and by which all the forms of things, and all the hidden springs of Nature, become intuitively known. Concerning this faculty the alchemists speak magisterially, as if it had illuminated their understanding so that they had entered into an alliance with the Omniscient Nature, and as if their individual consciousness had become one with Universal Consciousness. The first key of the Hermetic Mystery is in Mesmerism, but it is not Mesmerism working in the therapeutic sphere, but rather with a theurgic object, such as that after which the ancients aspired, and the attainment of which is believed to have been the result of initiation into the Greater Mysteries of old Greece. Between the process of these Mysteries and the process of Alchemy there is a distinctly traceable correspondence, and it is submitted that the end was identical in both cases. The danger which was the cause of the secrecy was the same also; it is that which is now connected with the Dwellers on the Threshold, the distortions and deceptions of the astral world, which lead into irrational confusion. Into this world the mesmeric trance commonly transfers its subjects, but the endeavour of Hermetic Art was a right disposition of the subject, not only liberating the spirit from its normal material bonds, but guaranteeing the truth of its experiences in a higher order of subsistence. It sought to supply a purely rational motive which enabled the subject to withstand the temptation of the astral sphere, and to follow the path upwards to the discovery of wisdom and the highest consciousness. There the soul knows herself as a whole, whereas now she is acquainted only with a part of her humanity; there also, proceeding by theurgic assistance, she attains her desired end and participates in Deity. The method of Alchemy is thus an arcane principle of self-knowledge and the narrow way of regeneration into life. Contemplation of the Highest Unity and Conjunction with the Divine Nature, the soul's consummation in the Absolute, lead up to the final stage, when the soul attains "divine intuition of that high exemplar which is before all things, and the final cause of all, which seeing only is seen, and understanding is understood, by him who penetrating all centres, discovers himself in that finally which is the source of all; and passing from himself to that, transcending, attains the end of his profession. This was the consummation of the mysteries, the ground of the Hermetic philosophy, prolific in super-material increase, transmutations, and magical effects."

It was impossible in the above synopsis, and is indeed immaterial at the moment, to exhibit after what manner the gifted authoress substantiates her theory by the evidences of alchemical literature. It is sufficient for the present purpose to summarize the interpretation of Alchemy which is offered by the Suggestive Inquiry.

The work, as many are aware, was immediately withdrawn from circulation; it is supposed that there are now only about twelve copies in existence, but as it is still occasionally met with, though at a very high price, in the book-market, this may be an understatement. Some ten years later, Eliphas Levi began to issue his course of initiation into "absolute knowledge," and in the year 1865 an obscure writer in America, working, so far as can be seen, quite independently of both, published anonymously a small volume of "Remarks on Alchemy and the Alchemists," in which it was attempted to show that the Hermetic adepts were not chemists, but were great masters in the conduct of life. Mr. Hitchcock, the reputed author, was not an occultist, though he had previously written on Swedenborg as a Hermetic Philosopher, and no attention seems to have been attracted by his work.

The interpretation of the Suggestive Inquiry was spiritual and "theurgic" in a very highly advanced degree: it was indeed essentially mystical, and proposed the end of Mysticism as that also of the Alchemical adepts. The interpretation of Eliphas Levi, who was an occultist rather than a Mystic, and does not seem to have ever really understood Mysticism, may be called intellectual, as a single citation will suffice to show.

"Like all magical mysteries, the secrets of the Great Work possess a three-fold significance: they are religious, philosophical, and natural. Philosophical gold is, in religion, the Absolute and Supreme Reason; in philosophy, it is truth; in visible nature, it is the Sun; in the subterranean and mineral world, it is most pure and perfect gold. It is for this cause that the search for the Great Work is called the search after the Absolute, and that the work itself passes as the operation of the Sun. All masters of the science have recognised that material results are impossible till all the analogies of the Universal Medicine and the Philosophical Stone have been found in the two superior degrees. Then is the labour simple, expeditious, and inexpensive; otherwise, it wastes to no purpose the life and fortune of the operator. For the soul, the Universal Medicine is supreme reason and absolute justice; for the mind, it is mathematical and practical truth; for the body, it is the quintessence, which is a combination of gold and light."

The interpretation of Hitchcock was, on the other hand, purely ethical. Now, as professedly an expositor of Mysticism, The Unknown World is concerned here only with the first interpretation, and with the clear issue which is included in the following question:- Does the literature of Alchemy belong to Chemistry in the sense that it is concerned with the disintegration of physical elements in the metallic order, with a view to the making of gold and silver, or is it concerned with man and the exaltation of his interior nature from the lowest to the highest condition?

In dealing with this question there is only one way possible to an exoteric inquiry like the present, and that is by a consideration of the literature and history of Alchemy. For this purpose it is necessary to begin, not precisely at the cradle of the science, because, although this was probably China, as will be discussed later on, it is a vexatious and difficult matter to settle on an actual place of origin; but for the subject in hand recourse may be had to the first appearance of Alchemy in the West, as to what. is practically a starting-point.

It is much to be deplored that some esoteric writers at this day continue to regard ancient Greece and Rome as centres of alchemical knowledge. It is true that the Abbe Pernety, at the close of the last century, demonstrated to his own satisfaction that all classical mythology was but a vesture and veil of the Magnum Opus and the fable of the Golden Fleece is regarded as a triumphant vindication of classical wisdom in the deep things of transmutation. But this is precisely one of those airy methods of allegorical interpretation which, once fairly started, will draw the third part of the earth and sea, and the third part of the stars of heaven, in the tail of its symbolism. Neither in Egypt, in Greece, or in Rome, has any trace of Alchemy been discovered by historical research till subsequent to the dawn of the Christian era, and in the face of this fact it is useless to assert that it existed secretly in those countries, because no person is in a position to prove the point. All that is known upon the problem of the origin of Alchemy in the Western Hemisphere is to be found in Berthelot's Collection des Anciens Alchimistes Grecs, and the exhaustive erudition which resulted in that work is summed up in the following statement:- "Despite the universal tradition which assigns to Alchemy an Egyptian Origin, no hieroglyphic document relative to the science of transmutation has yet been discovered. The Graeco-Egyptian Alchemists are our sole source of illumination upon the science of Hermes, and that source is open to suspicion because subject to the tampering of mystic imaginations during several generations of dreamers and scholiasts. In Egypt, notwithstanding, Alchemy first originated; there the dream of transmutation was first cherished;" but this was during and not before the first Christian centuries.

The earliest extant work on Alchemy which is as yet known in the West is the papyrus of Leide, which was discovered at Thebes, and is referable to the third century of this era. It contains seventy-five metallurgical formulae, for the composition of alloys, the surface colouration of metals, assaying, etc. There are also fifteen processes for the manufacture of gold and silver letters. The compilation, as Berthelot points out, is devoid of order, and is like the note-book of an artisan. It is pervaded by a spirit of perfect sincerity, despite the professional improbity of the recipes. These appear to have been collected from several sources, written or traditional. The operations include tinging into gold, gilding silver, superficial colouring of copper into gold, tincture by a process of varnishing, superficial aureation by the humid way, etc. There are many repetitions and trivial variations of the same recipes. M. Berthelot and his collaborator regard this document as conclusively demonstrating that when Alchemy began to flourish in Egypt it was the art of sophistication or adulteration of metals. The document is absolutely authentic, and "it bears witness to a science of alloys and metallic tinctures which was very skilful and very much advanced, a science which had for its object the fabrication and falsification of the matters of gold and silver. In this respect it casts new light upon the genesis of the idea of metallic conversion. Not only is the notion analagous, but the practices exposed in this papyrus are the same as those of the oldest Greek alchemists, such as pseudo-Democritus, Zosimus, Olympiodorus, and pseudo-Moses. This demonstration is of the highest importance for the study of the origines of Alchemy. It proves it to have been founded on something more than purely chimerical fancies- namely, on positive practices and actual experiences, by help of which imitations of gold and silver were fabricated. Sometimes the fabricator confined himself to the deception of the public, as with the author of Papyrus X (i.e., the Theban Papyrus of Leide), sometimes he added prayers and magical formulae to his art, and became the dupe of his own industry." Again: "The real practices and actual manipulations of the operators are made known to us by the papyrus of Leide under a form the most clear, and in acccrdance with the recipes of pseudo-Democritus and Olympiodorus. It contains the first form of all these procedures and doctrines. In pseudo-Democritus and still more in Zosimus (the earliest among the Greek alchemists), they are already complicated by mystical fancies; then come the commentators who have amplified still further the mystical part, obscuring or eliminating what was practical, to the exact knowledge of which they were frequently strangers. Thus, the most ancient texts are the clearest."

Now, there are many points in which the occultist would join issue with the criticism of M. Berthelot, but it is quite certain that the Egyptian papyrus is precisely what it is described to be, and there is, therefore, no doubt that the earliest work which is known to archaeology, outside China, as dealing with the supposed transmutation of metals is in reality a fraudulent business. This fact has to be faced, together with any consequences which it rigidly entails. But before concluding this paper it will be well to notice

(I.) That it is impossible to separate the Leide papyrus from a close relationship with its context of other papyri; as admitted by Berthelot, who says:- "The history of Magic and of Gnosticism is closely bound up with that of the origin of Alchemy, and the alchemical papyrus of Leide connects in every respect with two in the same series which are solely magical and Gnostic."

(II.) That, as Berthelot also admits, or, more correctly, as it follows from his admissions, the mystic element entered very early into alchemical literature, and was introduced by persons who had no interest in the practical part, who therefore made use of the early practical documents for their own purposes.

(III.) That the Leide papyrus can scarcely be regarded as alchemical in the sense that Geber, Lully, Arnold, Sendivogius, and Philalethes are alchemical writers. It neither is nor pretends to be more than a thesaurus of processes for the falsification and spurious imitation of the precious metals. It has no connection, remote or approximate with their transmutation, and it is devoid of all alchemical terminology. In itself it neither proves nor disproves anything. If we can trace its recipes in avowedly alchemical writers, as M. Berthelot declares is the case, then, and then only, it may be necessary to include alchemists in the category of the compiler of this papyrus.

The next stage of inquiry into the validity of the venous answers which have been given to this question will take us by an easy transition from the nature of the Leide papyrus to that of the Byzantine collection of ancient Greek alchemists. It will he recollected from last month that the processes contained in the papyrus are supposed to represent the oldest extant form of the processes tabulated by Zosinius, pseudo-Democritus. and others of the Greek school. The claims of this school now demand some brief consideration for the ultimate settlement of one chief point, namely, whether they are to be regarded as alchemists in the sense that attaches to the term when it is applied as advigoration of men like Arnold, Lully, and Schmurath. It was stated last month that the compiler of the Leide papyrus could not be so regarded, and it will, furthermore, pass without possible challenge that no person could accuse that document of any spiritual significance. The abbreviated formulae of a common medical prescription are as likely to contain the secret of the tincture or the mystery of the unpronounceable tetrad. In proceeding to an appreciation of the Greek alchemists, our authority will he again M. Berthelot, who offers a signal and, indeed, most illustrious instance of the invariable manner in which a genuine and unbiased archeologist who is in no sense a mystic can assist a mystic inquiry by his researches. M. Berthelot offers further a very special example of unwearied desire after accuracy, which is not at all common even among French savants, and is quite absent from the literary instinct of that nation as a whole. The fullest confidence may always be reposed in his facts.

The collection of Greek alchemists, as it now exists, was formed during the eighth or ninth century of the Christian era, at Constantinople. Its authors are cited, says Berthelot, by the Arabian writers as the source of their knowledge, and in this manner they are really the fountain-head of Western alchemy as it is found during the middle ages, because the matter was derived from Arabia. The texts admit of being separated into two chief classes, of which one is historical and theoretical, the other technical and covered with special fabrications, as for example, various kinds of glass and artificial gems. It is outside the purpose of an elementary inquiry to enumerate the manuscript codices which were collated for the publication of the text as it was issued by M. Berthelot in 1847. It is sufficient to say that while it does not claim to include the whole of the best alchemists, it omits an author who was judged to be of value either to science or archeology, and it is thus practically exhaustive. The following synthetic tabulation will be ample for the present purpose:- a. General Indications, including a Lexicon of the best Chrysopeia, a variety of fragmentary treatises, an instruction of Iris to Honris, &c. b. Treatises attributed to Democritus or belonging to the Democritic school, including one addressed to Dioscorus by Sycresius, and another of considerable length by Olympiodorus the Alexandrian philosopher. c. The works of Zosinius the Panopolite. d. A collection of ancient authors, but in this case the attribution is frequently apocryphal, and the writings in some instances are referable even to so late a period as the fifteenth century. Pelopis the philosopher, Ortanes, Iamthichers, Agathodamion and Moses are included in this section. e. Technical treatises on the goldsmith's art, the tincture of copper with gold, the manufacture of various glasses, the sophistic colouring of precious stones, fabrication of silver, incombustible nelphom, &c. f. Selections from technical and mystical commentators on the Greek alchemists, including $tephanus, the Christian philosopher, and the Anonymous Philosopher. This section is exceedingly incomplete, but M. Berthelot is essentially a scientist, and from the scientific standpoint the commentators are of minor importance.

The bulk of these documents represent alchemy as it was prior to the Arabian period according to its ancient remains outside Chinese antiquities, and any person who is acquainted with the Hermetic authors of the middle ages who wrote in Latin, or, otherwise, in the vernacular of their country, will most assuredly find in all of them the source of their knowledge, their method, and the terminology of the Latin adepts. For, on examination, the Greek alchemists are not of the same character as the compiler of the Leyden papyrus, though he also wrote in Greek. With the one as with the other the subject is a secret science, a sublime gnosis, the possessor of which is to be regarded as a sovereign master. With the one as with the other it is a divine and sacred art, which is only to be communicated to the worthy, for it participates in the divine power, succeeds only by divine assistance, and invokes a special triumph over matter. The love of God and man, temperance, unselfishness, truthfulness, hatred of all imposture, and the essential preliminary requisites which are laid down most closely by both schools. By each indifferently a knowledge of the art is attributed to Hermes, Plato, Aristotle, and other great names of antiquity, and Egypt is regarded as par excellence the country of the great work. The similarity in each instance of the true process is made evident many times and special stress is laid upon a moderate and continuous heat as approved to a violent fire. The materials are also the same, but in this connection it is only necessary to speak of the importance attributed to many of the great alchemists in order to place a student of the later literature in possession of a key to the correspondence which exist under this head. Finally, as regards terminology, the Greek texts abound with references to the egg of the philosophers, the philosophical stone, the same which is not a stone, the blessed water, projection, the time of the work, the matter of the work, the body of Morpresia, and other arbitrary names which make up the bizarre company of the mediaeval adepts. This fact therefore must be faced in the present enquiry, and again with all its consequences: that the Greek alchemists so far as can be gathered from their names were alchemists in the true sense of Lully and Arnold: that if Lully and Arnold are entitled to be regarded as adepts of a physical science and not as physical chemists, then Zosinius also is entitled to he so regarded: that if Zosinius and his school were, however, houseminters of metal, it is fair to conclude that men of later generations belong to the same category: that, finally, if the Greek alchemists under the cover of a secret and pretended sacred science were in reality fabricators of false sophisticated gold and riches, there is at any rate some presumption that those who reproduced their terminology in like manner followed their objects, and that the science of alchemy ended as it begun, an imposture, which at the same time may have been in many cases "tempered with superstition", for it is not uncommon to history that those who exploit credulity finish by becoming credulous themselves.

It is obvious that here is the crucial point of the whole inquiry, and it is necessary to proceed with extreme caution. M. Berthelot undertakes to shew that the fraudulent recipes contained in the Leyden papyrus are met with again in the Byzantine collection, but the judgment which would seem to follow obviously from this fact is arrested by another fact which in relation to the present purpose is of very high importance, namely, that a mystic element had already been imported into alchemy, and that some of those writers who reproduce the mystic processes were not chemists and had no interest in chemistry. Now, on the assumption that alchemy was a great spiritual science, it is quite certain that it veiled itself in the chemistry of its period, and in this case does not stand or fall by the quality of that chemistry, which, as M. Berthelot suggests, may very well have been only imperfectly understood by the mystics who, on such a hypothesis, undertook to adopt it. The mystic side of Greek alchemical literature will, however, be dealt with later on.

When the transcendental interpretation of alchemical literature was first enunciated, the Leyden papyruses had indeed been unrolled, but they had not been published, and so also the Greek literature of transmutation, unprinted and untranslated, was only available to specialists. This same interpretation belongs to a period when it was very generally supposed that Greece and Egypt were sanctuaries of chemical as well as transcendental wisdom. In a word, the origines of alchemy were unknown except by legend. Now this paper has already established the character of the Leyden papyrus numbered X. in the series, and it was seen that there was nothing transcendental about it. On the other hand, it was also stated that the Byzantine collection of Greek alchemists uses the same language, much of the same symbolism, and methods that are identical with those of the mediaeval Latin adepts, whose writings are the material on which the transcendental hypothesis of alchemy has been exclusively based, plus whatsoever may be literally genuine in the so-called Latin translations of Arabian writers. Does the Byzantine collection tolerate the transcendental hypothesis? Let it be regarded by itself for a moment, putting aside on the one hand what it borrowed from those sources of which the Leyden Papyrus is a survival, and on the other what it lent to the long line of literature which came after it. Let it be taken consecutively as it is found in the most precious publication of Berthelot. There is a dedication which exalts the sovereign matter, and seems almost to deify those who are acquainted therewith; obviously a spiritual interpretation might be placed upon it; obviously, also, that interpretation might be quite erroneous. It is followed by an alphabetical Lexicon of Chrysopeia, which explains the sense of the symbolical and technical terms made use of in the general text. Those explanations are simply chemical. The Seed of Venus is verdegris; Dew, which is a favourite symbol with all alchemists, is explained to be mercury extracted from arsenic, i.e., sublimed arsenic; the Sacred Stone is chrysolite, though it is also the Concealed Mystery; Magnesia, that great secret of all Hermetic philosophy, is defined as white lead, pyrites, crude vinegar, and female antimony, i.e., native sulphur of antimony. The list might be cited indefinitely, but it would be to no purpose here. The Lexicon is followed by a variety of short fragmented treatises in which all sorts of substances that are well known to chemists, besides many which cannot now be certainly identified, are mentioned; here again there is much which might be interpreted mystically, and yet such a construction may be only the pardonable misreading of unintelligible documents. In the copious annotations appended to these texts by M. Berthelot, the allusions are, of course, read chemically. Even amidst the mystical profundities of the address of Isis to Horis, he distinguishes allusions to recondite processes of physical transmutation. About the fragments on the Fabrication of Asem and of Cinnabar, and many others, there is no doubt of their chemical purpose. Among the more extended treatises, that which is attributed to Democritus, concerning things natural and mystic, seems also unmistakably chemical; although it does term the tincture, the Medicine of the Soul and the deliverance from all evil, there is no great accent of the transcendental. As much may be affirmed of the discourse addressed to Leucippus, under the same pseudonymous attribution. The epistle of Synesius to Dioscorus, which is a commentary on pseudo-Democritus, or, rather, a preamble thereto, exalts that mythical personage, but offers no mystical interpretation of the writings it pretends to explain. On the other hand, it must be frankly admitted the treatise of Olympiodorus contains material which would be as valuable to the transcendental hypothesis as anything that has been cited from mediaeval writers- for example, that the ancient philosophers applied philosophy to art by the way of science- that Zosinius, the crown of philosophers, preaches union with the Divine, and the contemptuous rejection of matter- that what is stated concerning minera is an allegory, for the philosophers are concerned not with minera but with substance. Yet passages like these must be read with their context, and the context is against the hypothesis. The secret of the Sacred Art, of the Royal Art, is literally explained to be the King's secret, the command of material wealth, and it was secret because it was unbecoming that any except monarchs and priests should be acquainted with it. The philosopher Zosinius, who is exalted by Olympiodorus, clothes much of his instructions in symbolic visions, and the extensive fragments which remain of him are specially rich in that bizarre terminology which characterized the later adepts, while he discusses the same questions which most exercised them, as, for example, the time of the work. He is neither less nor more transcendental than are these others. He speaks often in language mysterious and exalted upon things which are capable of being understood spiritually, but he speaks also of innumerable material substances, and of the methods of chemically operating thereon. In one place he explicitly distinguishes that there are two sciences and two wisdoms, of which one is concerned with the purification of the soul, and the other with the purification of copper into gold. The fragments on furnaces and other appliances seem final as regards the material object of the art in its practical application. The writers who follow Zosinius in the collection, give much the same result. Pelagus uses no expressions capable of transcendental interpretation. Ostanes gives the quantities and names the materials which are supposed to enter into the composition of the all-important Divine Water. Agathodaimon has also technical recipes, and so of the rest, including the processes of the so-called Iamblichus, and the chemical treatise which, by a still more extraordinary attribution, is referred to Moses. The extended fragments on purely practical matters, such as the metallurgy of gold, the tincture of Persian copper, the colouring of precious stones, do not need investigation for the purposes of a spiritual hypothesis, their fraudulent nature being sufficiently transparent, despite their invoking the intervention of the grace of God.

There is one other matter upon which it is needful to insist here. The priceless manuscripts upon which M. Berthelot's collection is based contain illustrations of the chemical vessels employed in the processes which are detailed in the text, and these vessels are the early and rude form of some which are still in use. This is a point to be marked, as it seems to point to the conclusion that the investigation of even merely material substances inevitably had a mystic aspect to the minds which pursued them in the infancy of physical science.

The next point in our inquiry takes us still under the admirable auspices of M. Berthelot, to the early Syriac and the early Arabian alchemists. Not until last year was it possible for anyone unacquainted with Oriental languages to have recourse to these storehouses, and hence it is to be again noted that the transcendental interpretation of Alchemy, historically speaking, seems to have begun at the wrong end. In the attempt to explain a cryptic literature it seems obviously needful to start with its first developments. Now, the Byzantine tradition of Alchemy came down, as it has been seen, to the Latin writers of the middle ages, but the Latin writers did not derive it immediately from the Greek adepts. On the contrary, it was derived to them immediately through the Syriac and Arabian Alchemists. What are the special characteristics of these till now unknown personages? Do they seem to have operated transcendentally or physically, or to have recognised both modes? These points will be briefly cleared up in the present article, but in the first place it is needful to mention that although the evidence collected by Berthelot shews that Syria and Arabia mediated in the transmission of the Hermetic Mystery to the middle age of Europe, they did not alone mediate. "Latin Alchemy has other foundations even more direct, though till now unappreciated... The processes and even the ideas of the ancient Alchemists passed from the Greeks to the Latins, before the time of the Roman Empire, and, up to a certain point, were preserved through the barbarism of the first mediaeval centuries by means of the technical traditions of the arts and crafts." The existence of a purely transcendental application of Alchemical symbolism is evidently neither known nor dreamed by M. Berthelot, and it will be readily seen that the possibility of a technical tradition which reappears in the Latin literature offers at first sight a most serious and seemingly insuperable objection to that application. At the same time the evidence for this fact cannot be really impugned. The glass-makers, the metallurgists, the potters, the dyers, the painters, the jewellers, and the goldsmiths, from the days of the Roman Empire, and throughout the Carlovingian period, and still onward were the preservers of this ancient technical tradition. Unless these crafts had perished this was obviously and necessarily the case. To what extent it was really and integrally connected with the mystical tradition of Latin Alchemical literature is, however, another question. The proofs positive in the matter are contained in certain ancient technical Latin Treatises, such as the Compositiones ad Tingenda, Mappa Clavicula, De Artibus Romanorum, Schedula diversarum Artium, Liber diversarum Artium, and some others. These are not Alchemical writings; they connect with the Leyden papyrus rather than with the Byzantine collection; and they were actually the craft- manuals of their period. Some of them deal largely in the falsification of the precious metals.

The mystical tradition of Alchemy, as already indicated, had to pass through a Syriac and Arabian channel before it came down to Arnold, Lully, and the other mediaeval adepts. Here it is needful to distinguish that the Syriac Alchemists derived their science directly from the Greek authors, and the Arabians from the Syriac Alchemists. The Syriac literature belongs in part to a period which was inspired philosophically and scientifically by the School of Alexandria, and in part to a later period when it passed under Arabian influence. They comprise nine books translated from the Greek Pseudo-Democritus and a tenth of later date but belonging to the same school, the text being accompanied by figures of the vessels used in the processes. These nine books are all practical recipes absolutely unsuggestive of any transcendental possibility, though a certain purity of body and a certain piety of mind are considered needful to their success. They comprise further very copious extracts from Zosimus the Panopolite, which are also bare practical recipes, together with a few mystical and magical fragments in a condition too mutilated for satisfactory criticism. The extensive Arabic treatise which completes the Syriac cycle, is written in Syriac characters, and connects closely with the former and also with the Arabian series. It is of later date, and is an ill-digested compilation from a variety of sources. It is essentially practical.

The Arabian treatises included in M. Berthelot's collection contain The Book of Crates, The Book of El-Habib, The Book of Ortanes, and the genuine works of Geber. With regard to the last the students of Alchemy in England will learn with astonishment that the works which have been attributed for so many centuries to this philosopher, which are quoted as of the highest authority by all later writers, are simply forgeries. M. Berthelot has for the first time translated the true Geber into a Western tongue. Now all these Arabic treatises differ generally from the Syriac cycle; they are verbose, these are terse; they are grandiose, these are simple; they are romantic and visionary, these are unadorned recipes. The book of El-Habib is to a certain extent an exception, but the Arabian Geber is more mysterious than his Latin prototype. El-Habib quotes largely from Greek sources, Geber only occasionally but largely from treatises of his own, and it is significant that in his case M. Berthelot makes no annotations explaining, whether tentatively or not, the chemical significance of the text. As a fact, the Arabian Djarber, otherwise Geber, would make a tolerable point of departure for the transcendental hypothesis, supposing it to be really tenable in the case of the Latin adepts.

Preceding papers have taken the course of inquiry through the Greek, Arabian, and Syrian literatures, and the subject has been brought down to the verge of the period when Latin alchemy began to flourish. Now before touching briefly upon this which is the domain of the spiritual interpretation, it is desirable to look round and to ascertain, if possible, whether there is any country outside Greece and Egypt, to which alchemy can be traced. It must be remembered that the appeal of Latin alchemy is to Arabia, while that of Arabia is to Greece, and that of Greece to Egypt. But upon the subject of the Magnum Opus the Sphinx utters nothing, and in the absence of all evidence beyond that of tradition it is open to us to look elsewhere. Now, it should be borne in mind that the first centre of Greek alchemy was Alexandria, and that the first period was in and about the third century of the Christian era. Writing long ago in La Revue Theasophique, concerning Alchemy in the Nineteenth Century, the late Madame Blavatsky observes that "ancient China, no less than ancient Egypt, claims to be the land of the alkahest and of physical and transcendental alchemy; and China may very probably be right. A missionary, an old resident of Pelun, William A. P. Martin, calls it the 'cradle of alchemy.' Cradle is hardly the right word perhaps, but it is certain that the celestial empire has the right to class herself amongst the very oldest schools of occult science. In any case alchemy has penetrated into Europe from China as we shall prove." Madame Blavatsky proceeded at some length to "compare the Chinese system with that which is called Hermetic Science," her authority being Mr. Martin, and her one reference being to a work entitled Studies of Alchemy in China by that gentleman.

When the present writer came across these statements and this reference, he regarded them as an unexpected source of possible light, and at once made inquiry after the book cited by Madame Blavatsky, but no person, no bibliography, and no museum catalogue could give any information concerning a treatise entitled Studies of Alchemy in China, so that these papers had perforce to be held over pending the result of still further researches after the missing volume. Mr. Carrington Bolton's monumental Bibliography of Chemistry was again and again consulted, but while it was clear on the one hand that Mr. Martin was not himself a myth, it seemed probable, as time went on, that a mythical treatise had been attributed to him. Finally, when all resources had failed, and again in an unexpected manner, the mystery was resolved, and Mr. W. Emmett Coleman will no doubt be pleased to learn- if he be not aware of it already- that here as in so many instances which he has been at the pains to trace, Madame Blavatsky seems to have derived her authority second-hand. The work which she quoted was not, as she evidently thought, a book separately published, but is an article in The China Review, published at Hong Kong. From this article Madame Blavatsky has borrowed her information almost verbatim, and indeed where she has varied from the original, it has been to introduce statements which are not in accordance with Mr. Martin's, and would have been obviously rejected by him.

Mr. Martin states (I) that the study of alchemy "did not make its appearance in Europe until it had been in full vigour in China for at least six centuries, or circa B.C. 300. (2) That it entered Europe by way of Byzantium and Alexandria, the chief points of intercourse between East and West. Concerning the first point Madame Blavatsky, on an authority which she vaguely terms history, converts the six centuries before A.D. 300, with which Mr. Martin is contented, into sixteen centuries before the Christian era, and with regard to the second she reproduces his point literally. Indeed, it is very curious to see how her article, which does not treat in the smallest possible degree of alchemy in the nineteenth century, is almost entirely made up by the expansion of hints and references in the little treatise of the missionary, even in those parts where China is not concerned. Mr. Martin, himself more honourable, acknowledges a predecessor in opinion, and observes that the Rev. Dr. Edkins, some twenty years previously, was the first, as he believes to "suggest a Chinese origin for the alchemy of Europe." Mr. Martin, and still less Dr. Edluns, knew nothing of the Byzantine collection, and could not profit by the subsequent labours of M. Berthelot, and yet it is exceedingly curious to note that the researches of the French savant do in no sense explode the hypothesis of the Chinese origin of alchemy, or rather, for once in a season to be in agreement with Madame Blavatsky, perhaps not the origin so much as a strong, directing, and possibly changing influence. The Greek alchemists appeal, it is true, to Egypt, but, as already seen, there is no answer from the ancient Nile, and China at precisely the right moment comes to fill up the vacant place.

The mere fact that alchemy was studied in China has not much force in itself, but Mr. Martin exhibits a most extraordinary similarity between the theorems and the literature of the subject in the far East and in the West, and in the course of his citations there are many points which he himself has passed over, which will, however, appeal strongly to the Hermetic student. There is first of all, the fundamental doctrine that the genesis of metals is to be accounted for upon a seminal principle. Secondly, there is the not less important doctrine that there abides in every object an active principle whereby it may attain to "a condition of higher development and greater efficiency." Thirdly, there is the fact that alchemy in China as in the West was an occult science, that it was perpetuated "mainly by means of oral tradition," and that in order to preserve its secrets a figurative phraseology was adopted. In the fourth place, it was closely bound up with astrology and magic. Fifthly, the transmutation of metals was indissolubly allied to an elixir of life. Sixthly, the secret of gold-making was inferior to the other arcanum. Seventhly, success in operation and research depended to a large extent on the self-culture and self-discipline of the alchemist. Eighthly, the metals were regarded as composite. Ninthly, the materials were indicated under precisely the same names: lead, mercury, cinnabar, sulphur, these were the chief substances, and here there is no need to direct the attention of the student to the role which the same things played in Western alchemy. Tenthly, there are strong and unmistakable points of resemblance in the barbarous terminology common to both literatures, for example, "the radical principle," "the green dragon," the "true lead," the "true mercury," etc.

In such an inquiry as the present everything depends upon the antiquity of the literature. Mr. Carrington Bolton includes in his bibliography certain Chinese works dealing with Alchemy, and referred to the third century. Mr. Martin, on the other had, derives his citations from various dates, and from some authors to whom a date cannot be certainly assigned. Now, he tells us, without noticing the pregnant character of the remark, that "one of the most renowned seats of Alchemic industry was Bagdad, while it was the seat of the Caliphate"- that an extensive commerce was "carried on between Arabia and China"- that "in the eighth century embassies were interchanged between the Caliphs and the Emperors"- and, finally, that "colonies of Arabs were established in the seaports of the Empire." As we know indisputably that Arabia received Alchemy from Greece, it is quite possible that she communicated her knowledge to China, and therefore, while freely granting that China possessed an independent and ancient school, we must look with suspicion upon its literature subsequent to the eighth century because an Arabian influence was possible. But, independently of questions of date, comparative antiquity, and primal source, the chief question for the present purpose is whether Chinese Alchemy was spiritual, physical, or both. Mr. Martin tells us that there were two processes, the one inward and spiritual, the other outward and material. There were two elixirs, the greater and the less. The alchemist of China was, moreover, usually a religious ascetic. The operator of the spiritual process was apparently translated to the heaven of the greater genii. As to this spiritual process Mr. Martin is not very clear, and leaves us uncertain whether it produced a spiritual result or the perpetuation of physical life.

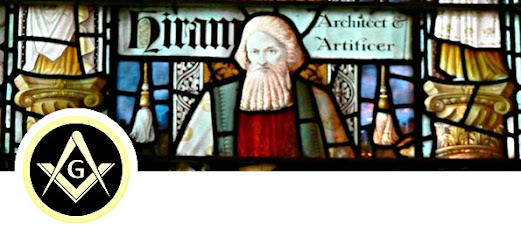

LA LÉGENDE D'HIRAM

Articles les plus récents

LES SENTIERS D’HERMÈS