|

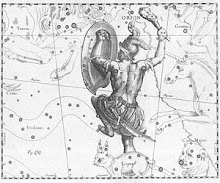

| Soma (Chandra), God of the Moon |

SPESS Soma and the Origins of Alchemy (Indian Alchemy).

SOMA AND THE ORIGINS OF ALCHEMY

Excerpt from

SOMA, THE DIVINE HALLUCINOGEN

By David L. Spess

(Chapter 5)

SOMA AND THE ORIGINS OF ALCHEMY

Evidence indicates that the Rig Vedic soma and soma ceremony

lie close to the origins of the world's alchemical traditions. To the best of

my knowledge this connection has never been discussed before. In fact, the

evidence suggests that the soma tradition may well be the oldest systematic

form of alchemy in the world.

India was known from ancient times to be in possession of

the elixir of immortality and the fountain of youth. It was even thought to be

the site of the earthly paradise and the beginning of the creation of life, as

well as the origin of the primordial first man. The origin of the English word

man is derived from the Sanskrit name Manu, the first man.

According to the Greek physician Ktesias, who served as

personal physician to the Persian king Artaxerxes Mnemon from 405 to 397

B.C.E., the fountain of youth was located in India. Ktesias says of the

inhabitants of India, "They are just, and of all men are the longest

lived, attaining the age of 170 and some even of 200 years."(1) According

to Middle Eastern tradition, Alexander the Great went to India to search for

the "water of life."(2) In 326 B.C.E. Nearchus, the admiral of

Alexander's fleet in India, described the Indians in his journals as healthy,

"free from disease, and living up to a very old age."(3) Onesikritus

of Astyplaia was the Greek pilot of Alexander's fleet. He also accompanied

Alexander into India and kept a journal of his experiences and observations. He

wrote that Indians "live 130 years without becoming old, for if they die

then they are cut off as it were in mid‑life."(4) Around 321

B.C.E., the Greek ambassador Megasthenes went to India and served for the

Seleucid Empire at the court of Chandragupta. Megasthenes wrote a book about

India based on firsthand observation in which he mentions the long life span of

Indians. He tells us that the Greek myth of the Hyperboreans was of Indian

origin. He mentions that these Indian Hyperboreans "live a thousand

years." He also says that wine was never drunk by the Indians except at

sacrifices when soma juice was consumed. This indicates that at this time soma

was a fermented drink.' Sedlar speculates that the Greeks did not use the term

soma to avoid confusion because it meant "body" or "corpse"

in Greek.(6) There is also evidence among the Greek historians that the Indians

used some form of supernatural means to rejuvenate themselves and to heal the

sick. Arrian, a Greek historian and philosopher born toward the end of the

first century C.E., compiled from the most reliable sources an account of the

Asiatic expedition of Alexander the Great. He noted that when the Greeks felt

"themselves much indisposed, they applied to their sophists [Brahmins] who

by wonderful, and even more than human means, cured whatever would admit of

cure."(7)

As early as the third century B.C.E., Chinese tradition

tells of the emperors of China sending expeditions into India and the West in

search of the fabled paradise, the plant of immortality, and the elixir of

life.(8) There is ample evidence that early Chinese knowledge of the Indian

soma motivated the searches of the emperor Ch'in Shih Huang‑ti of

the Ch'in Dynasty (249‑210 B.C.E.) and the emperor Wu‑ti

of the Han Dynasty (202 B.c.E. 220 C.E.) for the elixir of immortality.(9) Much later, the Chinese pilgrim Pahiyan,

while visiting India around 405‑411 C.E., was told by the Indian

priests that Indians of former ages had long life spans.(10)

Many centuries later the same idea of a miraculous method of

increasing longevity found only in India was restated by Marco Polo after his

visit to India, circa 1280 C.E. He wrote, "They live to a great age, some

of them even to 150 years, enjoying health and vigour . . . although they sleep

upon the bare earth."(11)

The location of the original paradise, of the original

homeland of mankind, and of the secret of immortality has intrigued humanity

for millennia. The original paradise or the Garden of Eden has always been

associated with longevity and immortality. Knowledge of the discovery in India

of the elixir of immortality and the original Eden of the Bible had reached

Europe at least by the twelfth century. Many church fathers and leaders

expressed the idea that the original paradise, fountain of youth, and the

origin of man were located in India. Some examples are from Saint Athanasius,

bishop of Alexandria (300 C.E.), who stated in his Questionary, "We are

taught that paradise was to the East .... For this reason, say the accurate

historians, fragrant spices are found in the orient in the direction of India .

. . ." Saint Jerome (375 C.E.) pictured paradise as lying somewhere north

of India in the Himalayas. In speaking of the original river of paradise that

split into four rivers, he writes in his De sita et nommibus that "Phison

is the river which our Greek scholars call the Ganges. This river pours out of

paradise and flows around the regions of India, and finally into the Indian

Ocean." In his De paradiso, Saint Ambrose, archbishop of Milan (400 C.E.),

says, "Paradise was planted in the Orient‑in a

place of delights." He says its source is the Ganges that flows around

India.

Legends about India became widely circulated throughout

Europe. It was said that not only the fountain of youth but also the much

sought‑after origin of creation, the land of Eden, the earthly

paradise, was to be found in India. This Indian paradise contained a fountain

of youth from which flowed the water of life that could heal the sick and

rejuvenate the aged. Europeans were eager to find this place. If the legends

were true, then this fountain in paradise would be the key to Adam's longevity

and the source of bodily immortality.

In the twelfth century, Hugo of Saint Victor (d. 1142 C.E.)

placed the earthly paradise in the East along with its tree of life and

fountain of youth:

Asia has many provinces and regions whose names and

locations I shall set forth briefly, beginning with paradise. Paradise is a

place in the East, planted with every kind of timber and fruit trees. It

contains the tree of life. No cold is there nor excessive heat, but a

constantly mild climate. It contains a fountain which runs off in four rivers.

It is called paradise in Greek, Eden in Hebrew, both of which words in our language

mean a Garden of Delight. (12)

It is interesting that in the Rig Vedic soma ceremony four

rivers are mentioned. These are the four rivers of paradise that branch off

from the single river, which is symbolic of the central pillar/tree of light

produced by soma during the ceremony. These rivers of light, equated with a

timeless paradise and the fountain of youth, are created by the soma flow at

the center of the world where the ceremony is being conducted.

Earlier legends mentioned by Ktesias clearly state that the

fountain of youth was located in India. Later, Dion Chrysostom (d. 117 c.E.),

in his Oratio (25.834), states that the Brahmans of India "possess a

remarkable fountain" of youth. Other legends, such as those of Prester

John, the mythical Eastern Christian king, also describe paradise as being in

India. The paradise of Prester John contained a fountain of youth "which

preserves health for three hundred and three years, three months, three weeks,

and three days."'(13) Not only the Christian but also the Islamic

tradition placed paradise in India. According to traditions current among the

Muslims, Adam, the first man, called manu or man in Sanskrit, originally

descended from heaven to India and received his first revelation there.(14)

All of these stories, myths, and legends are connected to a

variety of traditions that existed in ancient India. The source of these

legends lies in the traditions and ancient stories in the Rig Veda that discuss

rejuvenation. The rejuvenation stories found in the Rig Veda are the oldest

written sources that we possess concerning the rejuvenation of humans rather

than gods, goddesses, or serpents.(15)

The Rig Vedic soma ceremony also appears to be the oldest

preserved document in which human beings attain immortality while still living

in a physical body. The only exception to this is Utnapishtim, who lived with

the gods in Dilmun in the garden of the sun and was made immortal after the

flood. Another source for the legends derives from eyewitness accounts of

travelers exposed to the sages and the long traditions of the saints of India

who were renowned for such supernatural abilities as healing the sick,

rejuvenating the aged, and personal immortality. The genesis of such stories is

the logical outcome of the cosmogony and cosmology developed by the ancient

Indians in their earliest literature. This cosmology allowed for the existence

of a fundamental constituent of the universe, derived from the source of

creation, that could nourish and rejuvenate matter. This special substance was

called soma. It maintained the rejuvenating abilities of not only plant and

human life, but the earth, sun, moon, planets, and the eternity of the universe

as a whole. These early ideas led to the notion that the earthly paradise, the

fountain of youth, and the water of life were to be found in India. The origin

of these ideas in their fully developed forms are directly connected to the

earliest soma ceremonies described in the Rig Veda.

Widespread knowledge of soma as an elixir of immortality or

"water of life" demonstrates its emergence and diffusion throughout

the Rig Vedic period and must be at least as old as the oldest hymns, if not

older. This would date the soma system of alchemy to around 1800 B.C.E. and

make it the oldest developed form of elixir alchemy known. The rituals of the

soma ceremony, and soma itself, are used for mystical union and healing in the

Rig Veda, and they form the foundation of the beliefs in rejuvenation and

healing in portions of the Artharva Veda. The soma alchemical system forms the

basis of the later alchemical, rasayana, and Ayurvedic schools of India. Parts

of this system are also incorporated into the different techniques of yoga and

tantra in the Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist schools.

ORIGINS OF THE ELIXIR THEORY OF ALCHEMY

The "water of life" is infrequently mentioned in

Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian, and Egyptian texts, and it does not appear to have ever been developed in these cultures into either an herbal or specific

internal alchemical system as soma was. Nor did mortals ever obtain the

immortal status of the gods as they did after drinking soma in the Rig Veda. The

old Indo‑European mead drink reached its fullest development in

Indo‑Iranian

rituals as the ambrosia of the gods. This is specifically true of the Indo‑Aryan

soma, which became I lie drink of both the gods and human beings. A number of

Rig Vedic hymns clearly state that at one time only the gods gained immortality

through drinking soma. But through supernormal means, the Atharvans (soma

priests) discovered the gods' ancient secret of the preparation of the

entheogenic soma drink that allowed human beings to obtain the same immortal

status as the gods.

The notion of a substance such as the water of life, later

called an alchemical elixir, was systematically formulated among the

Indo-Iranians at an early date, possibly as early as 3500 B.C.E. It was the

Vedic Aryans, the originators of Sanskrit, the "language of the

gods," who called this elixir soma, a Sanskritized form of the Avestan

haoma drink, and who advanced this elixir idea to a fully developed internal

system of alchemy. The priests of the Rig Veda considered the celestial elixir

that flowed through the trunk of the cosmic tree to be the universal panacea,

the water of life that could heal, rejuvenate, and give immortality directly.

Interestingly, the theory of an elixir of life did not originally exist in

other forms of alchemy that were to develop many centuries later throughout the

world. There is strong evidence that the elixir theory in early alchemical

traditions was transmitted to these traditions from the early Indo‑Iranian

sacrificial rituals of soma and haoma. The Indian soma, more so than its

counterpart haoma, was much further developed as the internal elixir and was

transmitted to subsequent alchemical traditions. Soma was the original healer,

rejuvenator, and life‑span extender of ancient

civilization. The soma of the Aryans described in the Rig Veda is the source of

the notion of the elixir of life that influenced the development of the

alchemical elixir vitae in such diverse cultures as China, Islam, and Europe.

The transmutation of base metals into gold may have originated elsewhere;

however, there is early and clear evidence that this notion may also have come

from the Indo‑Iranian sacrificial rituals. This evidence can be clearly

seen in the Rig Vedic soma ceremony in its teaching of the internal method for

inducing paranormal abilities such as psychogenesis (mind‑born

creations or transmutations). Current research has suggested that elixir

alchemy was first developed in China among the Taoists. It can be shown,

however, that Chinese elixir theories were derived from the elixir theory in

India that came from the Rig Veda. The notion of a rejuvenating elixir appears

to have been transmitted to China from India at a very early date and from the

Chinese and Indians to the Arabs, from which it was transmitted through Arabic

alchemical and scientific writings to Jewish philosophers and to Roger Bacon,

who disseminated this information throughout Europe around 1250 C.E.16 Joseph

Needham shows that soma was the original alchemical elixir of life in Indian,

Chinese, Middle Eastern, and European alchemical texts. Some of these

influences came directly from the Rig Veda soma ceremony of the Brahmans and the

Atharva Veda while others were by way of later Hindu and Buddhist religious and

philosophical texts.

My purpose is to show how Indian religion and philosophical

doctrines derived from the Rig Vedic soma ceremony have influenced Chinese,

Greco‑Egyptian,

and Islamic alchemy, and how they became incorporated into European alchemical

texts, practices, and lore.

SOMA AND CHINESE ALCHEMY

Chinese alchemy is primarily concerned with prolonging life

and the search for the elixir vitae. As noted above, this search for an elixir

was carried out by the rishis of the Rig Veda and other Indian ascetic groups

dating back to at least 1800 B.C.E. Some of the practices developed by these

sages were completely internal, while others used triggers such as entheogens

in conjunction with breathing, sound and visualization practices. The groups of

ascetics known as the Munis and the Kesins, whose names in Sanskrit mean

"silent, long‑haired sages," have a special and powerful hymn

written about them in the Rig Veda. They were great miracle workers who

internalized the concepts of the soma sacrifice and perfected the uniting of

the opposites of fire and water. By internalizing the soma sacrificial

concepts, these ascetics were able to develop a subtle body, identified with

the sun as the cosmic pillar/tree, through which they attained immortality. As

described in the Rig Veda, this solar body was said to exit and return to the

physical body, and it was through this solar body that the alchemical elixir

soma was drunk. Their deity was the fierce god Rudra, lord of plants. Known as

the "red howler," Rudra is directly connected with Indra, Soma, and

the sun. The Rig Vedic Maruts are Rudra and Indra's companions, and they are

associated in both the Rig Veda and the Atharva Veda with the seven vital

breaths that howl like a whirlwind when leaving the body. The Munis and Kesins

used various herbal concoctions to produce states of ecstasy and were able to

leave the body at will.

Another early ascetic group, called the vratyas, were great

miracle workers. They internalized the principles of the soma ceremony and

practiced special forms of ascesis that are still not completely understood.

The vratyas, who were herbal alchemists, also worshipped Rudra, lord of plants.

They are said to have searched for and found the elixir of life." Their

ascesis involved not just the mortification of the physical body, but a

practice based on the internal vibrations (vipra) within the matrix (hrdyakasa,

or space within the heart), the universal womb of creation associated with the

Anthropos. Their practices involved a combination of fasting, breath control,

entheogenic drug use, and the internal repetition of phonemes. They entered

ecstatic states and cosmicized their subtle bodies into replicas of the

universe.

Both Indian ascetics and early texts such as the Rig Veda,

Atharva Veda, and the Upanisads, as well as Buddhism, influenced the

development of Chinese alchemy. In both the Rig Veda and the Atharva Veda, the

elixir was associated with gold, the imperishable solar metal. The emphasis of

the Chinese alchemists was placed upon making gold, a substance that would confer

longevity or immortality to the body. This idea does not appear to enter

Western alchemy until the Islamic period.

Legend has it that Chinese alchemy originated in the

teachings of the naturalist school, whose founder was Zou Yan (300 B.C.E.). The

naturalist school propagated the yin‑yang and five‑element

theory, but that the idea of an "elixir of immortality" developed

from their doctrines without outside influence cannot be shown. As will be

discussed later, from before the time of the development of the naturalist

school, there was a direct influence upon the development of Chinese alchemy

from Indo‑Iranian sources with regard to the plant of immortality

and the "elixir of life." The oldest treatise in China devoted

entirely to alchemy is the Cantongqi by Wei Bo‑yang,

which dates only to about 142 C.E.(18) Taoism, however, can be traced back to

its founder, Lao‑tzu, who lived around the fourth century B.C.E.'9 Taoist

alchemy, much like its Indian counterpart, became associated with all manner of

wonder‑working and magic. Early on, its attention was focused on

the problem of mortality. By bringing the body into a perfect harmony with the

Tao, the way of the universe, the body would acquire the attributes of the Tao

and so become deathless. The concept of the Tao is not different from the Rig

Vedic concept of rta, the foundation of eternal order, the principle of

universal harmony and balance at the cosmic center of being. This principle

operates throughout all of nature in both its animate and inanimate forms.

There are many similarities between the Rig Vedic soma and

Chinese alchemy. In both Chinese alchemy and European alchemy, the elixir or

philosopher's stone undergoes various color changes to reach perfection. The

soma of the Rig Veda goes through similar color changes during the soma

ceremony, including black, symbolic of primal matter before creation, and then

various shades of white, gold, red, and purple or rainbow colors. In the soma

ceremony, the color of the soma juice was alchemically altered by the priests

from white before dawn to a golden color after dawn until midday (by the union

of white and reddish yellow) and then to reddish yellow in the evening. These

same color changes in the matter of the philosopher's stone are found in

Chinese, Islamic, and European alchemy.

In China the language of alchemy was applied to various

techniques of breath control whose aim was also physical immortality. The goal

of the practices was the resurrection of the integral personality in a new and

imperishable body form, a body of light. In Chinese alchemy this special body

was nurtured like an embryo within the physical body by yogic disciplines. The

European alchemist, working along the same lines, brings an elixir to maturity

in a matrix of lead. The development of a new, embryonic, imperishable body

inside the physical body is derived from the soma ceremony of the Rig Veda,

Within the matrix of the heart‑cave‑womb

in the soma ceremony a golden embryo is generated that becomes the internal

body of light or Anthropos.

Special breathing techniques are first encountered in the Rig

Vedic soma ceremony with the chanting of sacred syllables by the rsis and

during their practice of generating internal heat and light. The Rig Vedic hymns

were written in a variety of magical chanting meters. The rhythmic monotony of

these incantations was accompanied by breathing techniques specific to each

meter; the method of chanting each meter was a well‑kept

secret. The ritual development of the embryonic alchemical sun within the womb

is a special part of the Rig Vedic soma ceremony that employed special breathing

techniques (tapas) associated with fire and sound. In the Atharva Veda there

are detailed examples of methods of embryonic womb breathing. The healing power is said to reside in the breath,

remaining latent until stimulated according to the established magical ritual.

A number of Chinese alchemists used Indian breathing

(Sanskrit prana, Chinese chi) techniques in their practices. Some of these are

Lu Pu‑wei

(d. ‑237

B.C.E.), Liu An (d. 122 B.C.E.), and Hua T'o (189 C.E.). Hua T'o was a famous

physician and master of life energy (chi). Hua T'o's techniques have been shown

to be derived from India. Even his name is derived from a transliteration of a

Sanskrit word for medicine, agadya, which means "universal cure‑all."(20) Breathing techniques themselves are a very

ancient tradition in China, certainly older than Chinese alchemy itself.

(21) Even though breath or chi control

practices were being used in China already in the sixth century B.C.E.(22) the Indian counterpart to such practices

dates from the hymns in the Rig Veda, Atharva Veda, Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and

Upanisads, which places the use of these techniques in India at least before

1200 B.C.E. And since the generation of the solar embryo with special breathing

techniques is present in the early development of the Rig Vedic soma ceremony as

an integral component, this could push the above date back to 1800 B.C.E. or

even earlier. Portions of the Atharva Veda can be dated to before 1150 B.C.E.

by the mention of iron in the text. Other parts are much older and incorporate

yoga‑type

practices, breathing techniques, and medicinal knowledge from indigenous Indian

cultures.

The great French Indologist Jean Filliozat addressed the

question of whether Taoist breath control antedates the corresponding Indian

yogas. He suggests that while each system is peculiar to its culture, there are

too many similarities to argue entirely independent development. At the same

time, he is convinced that such common elements as the concern with retention

of the pneuma or breath and the use of certain positions go back too far in

India and must have been imported directly into China.(23)

The embryonic respiration described in Taoist texts is more

like the early forms found in the Rig Vedic soma ceremony and must be derived

from the latter. As noted by Mircea Eliade, "The embryonic respiration (of

the Chinese) was not, therefore, like pranayama, an exercise preliminary to

meditation, nor an auxiliary technique, but sufficed in itself . . . to set in

motion and bring to completion a `mystical physiology' which led to the

indefinite prolongation of life of the material body."(24) This is exactly

what we find as the goal of the creation of the subtle body in the Rig Vedic

soma ceremony. Within the creative matrix of the universal womb the golden

embryo is nurtured and brought to full development. It does not involve a

continued pranayama regimen of breathing exercises, yet internal fiery breath

within the womb plays a vital part. These techniques may have been part of the

religious practices of the Indus Valley cultures (2700 B.C.E.), where seal

impressions have been found that depict sages seated in yogic postures. It is

now known that the Indus Valley cultures were in direct contact with central

Asia (Bactria), which was the original homeland of the Indo‑Iranians.

In the Rig Veda itself womb breathing is associated with the ecstasy states of

the soma ceremony and the heart‑sun‑womb of one's internal being.

The drawing in and breathing out of rays as breaths from the solar heart is a

basic component of the practice described there.

As we have shown, there is overwhelming evidence that the

Chinese Taoist rejuvenation and longevity techniques have their origin in the

Rig Veda and Atharva Veda, which far predate any Chinese Taoist or alchemical

texts. The soma ceremony described in both the Rig Veda and the Atharva Veda is

the source of the elixir theory, the practice of embryonic womb breathing,

various psychogenic processes, other breathing exercises, and the concept of

the breath as an energy source in the universe.

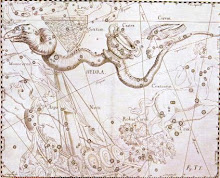

Another important idea derived from the Rig Vedic soma

ceremony is the association between the Pole Star and Big Dipper and the

heavenly elixir and rejuvenation and longevity concepts. The Pole Star and Big

Dipper figure in the archaic myths of most cultures, but their use as the

source and holder‑of the elixir of immortality in a developed cosmogony and

cosmology comes from the soma ceremony of the Rig Veda. In India from an early

date, kingship was associated with the Pole Star in an older form of cosmology

involving the deity Varuna.

There is evidence in the Indus Valley culture and in the Rig

Veda that associates not only Varuna but also Indra and Soma with the Pole

Star. Indra, the main deity of the hymns who plays an essential role in the

soma sacrifice, actually replaces Varuna as the Pole Star during the soma

ceremony: Varuna is said to become Indra.(25)

In China, according to Confucian philosophy, the Pole Star

was also associated with kingship. Both the Pole Star and the Big Dipper are

prominent aspects of Taoist alchemical techniques, and it is highly likely that

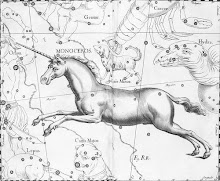

their source can be found in the hymns of the Rig Veda (Fig. 5).

Furthermore, certain alchemical texts of China have been

directly borrowed from Indian alchemical texts. An example of this is the

writing of the third‑century‑C.E. alchemist Ko‑Hung,

surnamed Paop'u tzu, who borrowed from the Buddhist Nagarjuna's Rasaratnacara.

In addition to borrowing Indian alchemical knowledge, Ko‑Hung

discussed certain miracles that could be performed through consumption of the

elixir, including walking on water and levitation.(26) These two feats have

only one source, the Indo‑Aryan Rig Veda somapa tradition. They

never occurred in China prior to their introduction from India. These miracles

were probably incorporated into alchemical texts from Buddhist sources.

The ancient Indo‑Iranian soma/haoma rituals have been

shown by Joseph Needham to have had a direct influence on the development of

Chinese alchemy. In addition to these early influences, there was continuous

contact with India through Hindu and Buddhist envoys, as recorded in Chinese

history. This contact included Hindu envoys of 105 B.C.E., 89 B.C.E., 159 C.E.,

and 161 C.E., as well as the introduction of Buddhism around 2 B.C.E. or

before. It was during this span that Indian alchemical texts as well as texts

on respiration were translated into Chinese.27 Further proof that India was the

source of the elixir comes from the Han emperors, who, upon asking for

instruction in the Buddhist faith, first requested that the Buddhists supply

them with the "herbal elixir of immortality," which only India was

known to possess.(28) In India, however,

the elixir ideas associated with immortality were more greatly developed than

in the Iranian Avesta. As mentioned by Lu Gwei‑Djen,

India appears to have been the original influence upon Chinese alchemy's

development of physiological alchemy or nei tan, which is a quasi‑yogistic

system of internal alchemy in which an elixir of immortality is synthesized

within the body of the alchemist .(29) The ancient soma plant of the Rig Veda

also had an influence on the development of Chinese herbal alchemy. Chinese

sages are known to have sought a special plant in India‑which

had to be soma‑that was supposed to bestow healing, longevity, and

immortality. Not only did the Chinese emperors of the Ch'in and Han Dynasties

seek out the soma plant of India, but one of the oldest Chinese medical texts,

Pen‑ts'ao

Kang Mu, mentions a lotus plant called hung pai‑lien‑hua,

which was from a foreign country and considered the plant of immortality. We

can attribute the many parallels between Chinese alchemy and the elixir

theories of immortality found in early Indian texts directly to the influence

of Indian elixir theories on Chinese philosophy.

The Rig Vedic soma ceremony includes within itself cosmic

processes and cycles of creation, maintenance, and destruction that are models

for alchemical processes. The soma of the soma ceremony is a combination of

entheogenic plant juices and pneumatic development within the body of the

adept. The process of developing an etherealized subtle body within the heart

is the foundation of the soma ceremony. This imperishable body, which is able

to remain in the physical body or to leave it behind, is used for healing,

longevity, paranormal abilities, and immortality. The Atharva Veda is full of

hymns that tell of the leaving of the physical body through an internal,

golden, subtle form generated within the womb of the heart. This concept, and

the meaning of the soma ceremony as an early form of internal alchemy, has not

been fully appreciated or understood by scholars of the origins of alchemy.

The ritual processes of the soma ceremony not only developed

a special internal body in the adept but also gave the adept the capacity for

psychogenesis and other psychic abilities. We find in the soma ceremony that the

soma elixir not only creates an immortal subtle body of light but also is the

method by which miracles are conducted. In the soma ceremony there is a process

in which the mind and the heart are combined during the ritual in order to

access the matrix continuum called the skambha. The matrix continuum is the

creative, universal womb located within the heart of being. This continuum‑womb

is identical to the Islamic philosopher's egg, the internal elixir embryo of

Taoist alchemy, and the Hermetic vessel of European alchemy. These ideas

originally come from the Rig Vedic soma ceremony.(30) For example, Joseph Needham says that

"the alchemist undertook to contemplate the cycles of cosmic process in

his newly accessible form because he believed that to encompass the Tao with

his mind (or, as he would have put it, his mind‑and‑heart)

would make him one with it. That belief was precisely what made him a

Taoist."(31) This combining of

heart and mind is also central to the soma ceremony. "Looking at all the

evidence impartially, one cannot escape the conclusion that the dominant goal

of proto‑scientific alchemy was contemplative, and indeed the

language in which the elixir is described was ecstatic." (32) This also shows a close correlation to the

ecstatic states attained by the priests that are mentioned in the Rig Vedic soma

ceremonies.

The motivation of both the first emperor of the Ch'in

Dynasty, Ch'in Shih Huang‑ti, and Wu‑ti of

the Han Dynasty for seeking the elixir of immortality comes from Indo‑Iranian

sources,(33) and, more specifically, from the Rig Veda and the Atharva Veda,

where the ideas were formulated into a coherent system of internal alchemical

practice, a fact that is not the case for the Iranian Avesta.

The soma practices of India were all that was needed to

trigger the development of elixir alchemy in Taoist China. Joseph Needham has

mentioned that China in the Warring States, Chin, and Han periods would have

provided precisely the supersaturated solution from which elixir alchemy would

crystalize, given the right seed. Fifty years ago H. H. Dubs proposed that this

seed was knowledge of (or hearsay about) the Indo‑Iranian

plant used by priests in their sacrifices late in the second millennium B.C.E.

Called haoma by the Persians and soma by the Indians, its use must antedate the

Aryan invasions because it is firmly attested to by both Avestan and Vedic

sources. The juice of this plant was believed, as far as one can tell from the

phraseology of the hymns, to cure all diseases of body and mind and to confer

immortality. Dubs went on to suggest that the means of transmission to China

was through the Yueh‑Chih people, who occupied western Kansu down to the third

century B.C.E., and whose chief city was Kanchow (modern Changyeh). This is the

people, in fact, whose alliance Chang Chien went to seek in Han Wu‑ti's

time after they had moved further to the west. Thus Dubs envisaged an overland

transmission of the idea of the drug or plant of immortality from the Indo‑Iranian

cultural area to China early in the fourth century B.C.E., if not

before.(34) Evidently we have here

something far more concrete than the metaphors of the Greco‑Egyptian

protochemists, and something that would have supplied just the element

necessary to make the Chinese Taoist set of ideas gel into full elixir

alchemy.(35) How this could have come about, according to Needham, can be seen

most strikingly if we examine ancient Indian liturgical texts, where the

essential germ of alchemy is defined as the art of long life plus aurifaction,

noting, by the way, that the connection of the idea of eternal life with the

incorruptible metal gold was probably a good deal older. It is easy to say that

this connection must go back to the very first knowledge of the properties of

metals. When one looks for it in texts from ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia, there

is not much to be found. (36) What is much more important is the remarkable

fact that in ancient India gold was intimately bound up with the soma sacrifice

itself.(37) Such then, it would seem, is the background both of the "plant

of immortality" that Ch'in Shih Huang‑ti sought and the

alchemical gold that Li Shao‑Chun undertook to manufacture. Surely

some rumor or persuasion of a most compelling character, reaching China from

Indo‑Aryan

sources, turned divinity into philosophy, or, to speak more precisely,

liturgiology into protoscience.(38)

The Chinese continued to consider India as the main source

for the knowledge of the "elixir of life" and sent many missions

there in order to bring back specific persons who could prepare the elixir for

the emperor. In 648 C.E., the emperor T' ai Tsung sent to India the envoy Wang

Hsdan‑tse,

who brought back a Brahman named Narayanaswamy who was a specialist in

"prolonging life." In 664‑65 C.E. the Buddhist monk Hsiian‑chao

was ordered by Kao Tsung to bring from Kashmir one Lokaditya, who possessed the

herbal drug of longevity. Lokaditya remained at the Chinese court at least

until 668 C.E.(39)

India continued to influence Chinese alchemical ideas

through the introduction of Buddhism." After the development of Chinese

alchemy, the elixir ideas of soma and the soma ceremony continued to influence

other cultures, particularly Islam. The ideas of soma were passed on to Islam

indirectly through Chinese alchemy and directly by contact with India.

SOMA AND GRECO‑EGYPTIAN ALCHEMY

There are traditions that claim the origin of alchemy was in

Egypt. But like the Gnostic schools and the Hermetic literature, alchemy as

formulated in Egypt was a syncretic philosophical system developed from many

sources. The foundation of much of the spiritual dimension of Greco‑Egyptian

alchemy comes from Indo‑Iranian sources.

An important figure in Greco‑Egyptian

alchemy was Demokritos (460‑370 B.C.E.), who is said to have

traveled widely and is thought to have spent time in India.(41) Demokritos is recalled mainly as the founder,

with Leukippos, of the atomic theory, according to which all bodies are made of

atoms that are themselves complete, indivisible, simple, eternally existent in

empty space, but differing in form and magnitude, with proportional weight. All

change comes through combinations or dissociations of atoms in a purely

mechanical way. The atomic theory is closely associated with alchemy in its

creation and transmutation aspects. The atomic theory was already known in

India by the Ajivikas, an ascetic sect of miracle workers that existed before

and at the time of the Buddha, around 500 B.C.E. From what we know of his life,

Demokritos appears to have lived as an ascetic. It is very possible that he

obtained his atomic theory from India. He also believed in a void, a purely Rig

Vedic concept found in the soma ceremony and later taken over by the Buddhists.

In addition, he said that souls were soul‑atoms and that the soul

consisted of smooth spherical storms of fire, a concept directly related to the

fiery pneumatic body in the heart where the soul resides. These same ideas are

found among the theological concepts of the Ajivikas and are derived from the

soma ceremony.

Demokritos was interested in much more than atoms. An entire

a alchemical school formed around him and his ideas. The Greek author Pliny

consistently links Demokritos with the Magi of Persia. Pliny notes that

Demokritos wrote an important book about plants in which he says that he will

start with the magical wonder plants. According to Pliny, these magical plants

were first brought to the notice of the West by Pythagoras and Demokritos, who

invoked the Magi as their authority. The magical plants mentioned by Demokritos

mainly are connected with altered states of consciousness and are derived from

the haoma and soma plants of Persia and India.(42)

During the formulation of alchemy in Greco‑Roman

Egypt in the first and second centuries C.E., there were direct trade links

with India. A statuette found at Pompeii of the Hindu goddess Laksmi, who is

associated with the lotus plant, has been dated to this time .(43) According to Greek sources, the Persian

mystic and magus Ostanes (500 B.C.E.) was the first to explain both magic and

alchemy to the Greco‑Egyptians. According to Pliny, he was the first writer on

magic and a direct pupil of Zoroaster. Ostanes was obviously an Indo‑Iranian

well acquainted with the magical/alchemical rituals of the entheogenic haoma/soma

ceremonies.

Very important Greco‑Egyptian magicians and

alchemists were said to be Ostanes' disciples. These included "Maria the

Jewess," who wrote several important books on alchemy, as well as the

famous Demokritos himself.(44) One other

very influential writer associated with Greco‑Egyptian alchemy is

Poisidonius (135‑51 B.C.E.) from Apamea in Syria. He was head of the Stoic

school at Athens and was responsible for many Stoic doctrines. He blended

science with astrology, magic, and alchemy. He was directly influenced by Indo‑Iranian

thought and fused Greek philosophy with Indo‑Iranian sacrificial

mysticism.(45)

We find ideas identical to those of the Rig Vedic soma

ceremony in books ascribed to Ostanes. He describes seven gates through which

the goal of gnosis can be reached; he goes on to say that the land of Egypt is

superior to all others on account of its wisdom and knowledge. The people of

Egypt as well as those of the rest of the world, however, have need of the

inhabitants of Persia and cannot succeed in any of their works without the aid

that they draw from this country. All the philosophers who have devoted

themselves to the science of alchemy have addressed themselves to persons from

Persia whom they have adopted as brothers.(46)

The main ideas that were transmitted through Greece and

Egypt concern the Indo‑Iranian sacrificial rituals of

haoma/soma. These rituals involve an up‑and‑down

motion and circulation process, both within the human body and the greater

universe. The notion of up-and‑down movement is important in Greek

alchemy. It has a direct relationship to uniting the aspects of microcosm and

macrocosm. Another important part of the sacrificial rituals is the concept of

the spiritual water. The subtle water is the luminous soma energy or fiery

water. This water is both the source of the unification of opposites and the

ultimate goal of the alchemical quest. The sacrificial ritual unites the above

and the below and opens up the source of the light of lights. All of these

Greco‑Egyptian

alchemical operations take place within the bowl‑shaped

altar as the alembic‑womb of transformation. This universal matrix is located

at the cosmic center within the heart of being. An understanding of the Greek

alchemist Zosimos can be achieved only by an understanding of the Indo‑Iranian

sacrificial rituals, especially the soma ceremony. During the soma ceremony a

dismemberment and then a rememberment occur within the solar heart, the

Hermetic vessel. Within the heart as the alembic‑womb,

luminous rays of being are gathered together through the sensory channels and

alchemical creations and transmutations are formed within the oceanic‑pneumatic

matrix and projected from the heart outward into manifestation.(47)

SOMA AND ISLAMIC ALCHEMY

The Islamic world was affected by China, Greece, and India.

Both China and Greece had incorporated ideas about soma, and through direct

contact with India, the elixir theory entered Islamic thought, having a

measurable impact upon Islamic alchemy. Impressed with Indian learning, the

Arabs incorporated many Indian ideas into Islamic alchemical texts. Relations

between India and the Arabs go back far before the rise of Islam. From among

all the cultures with which the Arabs came into contact, they were most

impressed by the Greeks and the Indians. According to 'Amr b. Bahr al‑Jahiz

of Basra (d. 869 C.E.), "I have found the inhabitants of India to have

made great advancement in astrology and mathematics. In the science of medicine

also they are highly advanced. The Chinese do not possess the qualities which

they have .... With them originated mysticism and charms which counteract

poisons. The origin of astronomical sciences goes back to the

Indians."(48)

Another important Arabic author, the well‑known

historian al‑Ya Qubi (d. 900 C.E.), remarks, "The Indians are men

of science and thought. They surpass all other peoples in every science; their

judgement on astronomical problems is the best; and their book on this subject

is the Siddhanta which has been utilized by the Greeks as well as the Persians

and others. In the science of medicine their ideas are highly advanced . . .

."(49)

Still another great Arabic writer of the ninth century, Abu

Ma‑shay

al‑Balkhi

(d. 885 C.E.), says, "The Indians are the first (most advanced nation).

All the ancient peoples have acknowledged their wisdom and accepted their

excellence in the various branches of knowledge. The kings of China used to

call the Indian kings, `the kings of wisdom,' because of their great interest

in the sciences."(50)

Many Indian physicians came to Arabia and not only practiced

medicine but helped in the translation of Indian medical and philosophical

texts from Sanskrit to Arabic .(51) As

one Tamil work states, "One of the Siddhars of Tamilnadu, Ramadevar, says

in his work on alchemy that he went to Mecca, assumed the name of Yakub and

taught the Arabians the alchemical art. It is significant that some of the

purification processes and substances of alchemical significance are common to

both the Islamic and the Indian alchemy.”(52)

Living in the later part of the eighth century, Geber

(Jabir), an Arab alchemist and Sufi, is credited with the formulation of the

famous sulphur/mercury theory of alchemy. The sulphur/mercury theory is

probably of foreign origin, because it occurs in the oldest Chinese alchemical

text, Cantongqi, written in 142 C.E. by Wei Bo‑yang.

In India the theory can be traced back to the Rig Vedic soma ceremony, where the

Asvins produce a golden elixir composed of sun and moon lotus plants by the

union of Agni (fire) and Soma (water). Many eighth‑century

alchemical manuscripts written in Arabic, Syrian, and Persian abound in

references to the sulphur/mercury theory. Through their eventual translation

into Latin by European scholars around the beginning of the twelfth century

C.E., much of the academic knowledge of the Arabs, including the

sulphur/mercury theory, was transmitted to Western Europe. The sulphur/mercury

theory of alchemy was really an attempt to show in chemical terms the union of

opposite natures in the production of the Grand Elixir. In sixteenth‑century

Europe, the sulphur/mercury theory was expanded to include salt, which then

became known as the triune microcosm. These three principles form the backbone

of much of European alchemical speculation.

"According to Latin as well as Arabic books, Geber was

surnamed El‑Sufi, the Sufi. He acknowledges in his works the Imam

Jafar Sadiq (700‑765 C.E.) [the great Sufi teacher] as his master."

Geber "was for a long time a close companion of the Barmecides, the

viziers of Haroun el‑Rashid. These barmakis [as they were called] were

descended from the priests of the Afghan Buddhist shrines, and were held to

have at their disposal the ancient teaching that had been transmitted to them

from that area."(54) Geber's

philosophical views were no doubt greatly influenced by his contacts with the

Barmecides, who were also the priests of the fire temple of Balkh, located in

Harran, and associated with the Sabians. This reveals another source of Indian

alchemical ideas transmitted to the West through the teachings of the Sabians

of Harran, who had close relations with India. According to Al‑Masud,

the ancient Sabians went on pilgrimage in the land of Sindan to a temple of

Saturn, built by the Indian Mashan, in the city of Al‑Mansurah.

This city was situated in ancient times along the old channel of the Indus and

was called Brahmanabad by the Indians. It was about one hundred miles south of

the Indus Valley city of Mohenjo Daro.(55)

The knowledge the Barmecides transmitted was the ancient

wisdom of the Hindus and Buddhists. This information had come by way of the

various trade routes connecting Afghanistan to central Asia and India.

Shamanism, Hinduism, and Buddhism contributed to the formation of the wisdom of

the area.

The entire sulphur/mercury theory of alchemy has its

probable antecedents in the Indian philosophy of the Rig Veda. It was in the

alchemy of the soma ceremony that a structure was developed that created a

separation in the original unity of light, which was then restored by the

ritual of the soma ceremony. The symbolic union of fire and water, as

Agni/Soma, occurs within the heart of the priest during the ceremony in a

special alchemical process that culminates in a transmutation of being, granting

immortality on the one hand, and the actual abilities of psychogenic creation

and transmutation on the other.

The separation and union of the duality of Agni/Soma in the

Rig Veda is the origin of all Indian speculation on the union of opposites. It

is also the probable origin of the dualism found in Islamic alchemical texts.

This knowledge from India was probably transmitted to Islamic thought from

Greece and China, both of which had already been influenced by Indian

philosophy. As noted by H. E. Stapleton, "The dualistic Yin/Yang theory

found in Chinese alchemy and philosophy has been shown to be another influence upon

China from Indo‑Iranian sources. Dualist theories are much older in Indo‑Iranian

religion than in China."(56) This makes it likely that Indo‑Aryan

dualist theories of Agni/Soma are the original precursor of the sulphur/mercury

theory. It was also transmitted by direct influence from India itself.

Paracelsus later added salt to the sulphur/mercury duality for chemical

reasons; salt was also a substance that represented the body as the medium in

which the two contraries could unite.

European writers have looked on Geber as the founder of the

alchemical art, but recent research seems to show that alchemical books

attributed to him are another case of attributing the work of many hands to a

single legendary figure. Under Geber's name appear numerous treatises; most of

them are alchemical, but others cover medicine, astronomy, astrology, magic,

mathematics, music, and philosophy. All together they indeed constitute an

encyclopedia of the sciences. Still, it has recently been maintained that no

Arab author mentions Geber until two centuries after the time in which he was

supposed to have lived. It is now regarded as very probable that this vast body

of writings was composed by the members of a group that resembles in its

religious leanings the secret sect of nature philosophers who called themselves

Ikwan al‑Safa, a name that has been variously translated as the

"Brethren of Purity" or the "Faithful Friends." The

Brethren of Purity composed an encyclopedic collection of letters much

resembling the Geberian writings. We may suppose then that a sect with a strong

belief in the power of science to purify the soul ascribed the works of its

members to the legendary Geber.(57) In

other words, the Geberian writings, although not without a chemical basis, are

really concerned with spiritual alchemy and personal transmutation. This

follows closely the origin of alchemical ideas and their deep spiritual nature.

As the soma ceremony reveals, the alchemical processes are internal and

spiritual.

Indian sciences, therefore, came to play an important part

in the growth of the sciences in Islam, a part far greater than is usually

recognized. In zoology, anthropology, mathematics, astronomy, and in certain

aspects of alchemy, the tradition of Indian and Persian sciences was dominant,

as can be seen in the Epistles (Rasa'il) of the Brethren of Purity and the

translations of Ibn Muqaffa'. It must be remembered that the words magic and

magi are related, and that according to the legend, the Jews learned alchemy

and the science of numbers from the Magi while in captivity in Babylon

(58) It should also be noted, however,

that Ammianus Marcellinus, the great Roman historian of the fourth century,

tells us that the Magi or Persian priests derived their secret arts from the

Brahmans of India.(59) Parts of the Indo‑Aryan

Rig Veda are much older than any Iranian religious text. In fact, several

prominent scholars, including Thomas Burrows, have argued that an Indo‑Aryan

empire existed from northern Syria to the Indus Valley in ancient times. The

Iranian branch of the Indo‑Europeans moved into the Indo‑Aryan

territory at a later date as an intrusive element. Therefore, the Indo‑Aryan

soma ceremony may be older than the Iranian haoma ceremony from which it is

claimed to be derived. This is especially true if it contains components

derived from indigenous India and the Indus Valley cultures.

Islamic alchemy had both a chemical and spiritual side, but

it is the spiritual side that really seems to hold out the possibility of

transmutation. This idea was clear to many Islamic philosophers as well. The

spiritual side of alchemy, rather than just the physical practice, was first

revealed by Geber's contemporaries, such as Al‑Biruni

and Ibn Sina (Avicenna). Both are greatly respected in European alchemical

circles. These two adepts accepted the cosmological principles of alchemy while

rejecting the possibility of transmutation because of the lack of

evidence.(60) The cosmological ideas

that make up the spiritual aspects of alchemy are sound. This fact is a clue to

the possible spiritual foundations of transmutation, which probably antedate

the chemical practices, and the idea is further strengthened by the numerous

examples of yogis in India and Sufis in Islam being able to transmute any

substance into gold without any chemicals, but through the force of the heart

of being. The spiritual‑elixir ideas contained within Islamic

alchemical texts were to have an important impact upon European alchemy. In

addition, Indian ideas were to influence the cosmological structure of the

Judaic Kabbalah. These cosmogonic and cosmologic ideas then entered European

alchemical texts and made a significant impact upon Western alchemy.

Before discussing the purpose of soma in European alchemy,

however, it is important to backtrack a bit and see how soma influenced the

development of magic in the West.

NOTES

1. J. W. McCrindle (1881), pp. 18, 25, 31, 34, 61.

2. Budge (1899).

3. B. Puri (1939), p. 40.

4. J. W. McCrindle (1881), pp. 47 48.

5. J. W. McCrindle (1960), pp. 76 79; on soma as a type of

wine, see Rawlinson

(1926), p. 58.

6. J. Sedlar (1980).

7. Rooke (1813), p. 219.

8. J. Edkins (1900), p. 590.

9. J. Needham (1974), vol. 5, part 2, pp. 115, 121 22;

(1980), vol. 5, part 4, p. 504.

10. S. K. Lakshminarayana (1970), p. 26.

11. H. Yule (1920), vol. 2, pp. 365 66.

12. G. Boas (1948), pp. 160, 161.

13. E. W. Hopkins (1905), p. 12.

14. M. Z. Siddiqi (1959), pp. 30, 33, quotes from "Amr

b. Bahr al Jahiz of Basra (d.

869 c.E.) and from the Arabic book `Arab wa Hind ke

Ta'alluqat, pp. 3, 12, 71 72.

15. Serpents were known to rejuvenate themselves by shedding

their skin. In the Rig Veda soma is also compared to a serpent that sheds its

skin and rejuvenates itself.

16. J. Needham (1974), vol. 5, part 2, pp. 492 98; see also

J. Needham (1981).

17. V. Karmarkar (1950), p. 25.

18. H. P. Yoke (1982), p. 35.

19. L. Kohn (1993), p. 4.

20. O. S. Johnson (1928), pp. 47 50; K. J. DeWoskin (1983),

pp. 18, 140 53, 188n.127.

21. The classic explication of immortality as the goal of

breath control is found in H. Maspero

(1981), pp. 459 554; see also N. Sivin (1968), pp. 31 32.

22. J. Needham (1983), vol. 5, part 5, p. 280.

23. J. Filliozat (1949), pp. 113 120.

24. M. Elude (1958), p. 59; J. Needham (1983), vol. 5, part

5, p. 288.

25. RV 4.42.3.

26. L. Wieger (1969), pp. 395 97, 401, 403, 405.

27. W. E. Soothill (1925), pp. 16, 18; L. Wieger (1969), p.

367.

28. J. Filliozat (1969), p. 46.

29. L. Gwei Djen (1973), p. 72.

30. J. Needham (1980), vol. 5, part 4, pp. 292 300,

discusses the egg, womb, and elixir

embryo.

31. Ibid., p. 245.

32. Ibid., p. 244.

33. W. Bauer (1976), pp. 91, 104, 159, 165, 390.

34. H. H. Dubs (1947), p. 62; J. Needham (1974), vol. 5,

part 2, p. 115.

35. J. Needham (1974), vol. 5, part 2, p. 117.

36. Ibid.

37. Ibid., p. 118.

38. Ibid., p. 121.

39. A. Waley (1930), pp. 22 23.

40. A. Waley (1932), p. 1102; J. Needham (1983), vol. 5,

part 5, pp.22 23: "Waley then pointed out how in later times Taoist nei

tan alchemy was much influenced by Buddhism, especially of the Chhan or Zen

School, as the case of Ko ChhangKeng, also known as Pai Yu Chhan, whose Hsiu

Hsien Pien Huo Lun (Resolution of Doubts Concerning the Restoration to

Immortality) written about +1218, shows explicitly. Thus Waley touched the very

essence of the matter by demonstrating that alchemical terminology had been

transferred from a specifically chemicalmetallurgical context to a psycho

physiological one, nei tan `elixirs' and their components not being in

crucibles or retorts but in the actual organs and vessels of the human body."

41. J. Lindsay (1970), p. 93.

42. Ibid., pp. 97 101

43. Ibid., p. 101.

44. R. Multhauf (1966), pp. 83 84, 114.

45. F. Cumont (1912), p. 58.

46. J. Lindsay (1970), p. 150.

47. Ibid., p. 345.

48. M. Z. Siddiqi (1959), pp. 32 33.

49. Ibid., p. 33 34.

50. Ibid., p. 34.

51. Ibid., pp. 34 35.

52. D. M. Bose (1971), p. 318, quoting from Ramadevar's

Cunnakandam, 227, 466.

53. H. P. Yoke (1982), p. 35.

54. 1. Shah (1964), pp. 194, 196.

55. H. E. Stapleton (1927), pp. 389 411.

56. H. E. Stapleton (1953), p. 17, n. 30, 38. This is an

important point because dualist theories make up the basis of both alchemical

theory as well as the Indo Aryan soma sacrifice, which indicates that Indo

Iranian cosmological ideas underlie the very foundations of alchemy.

57. F. S. Taylor (1949), pp. 78 79.

58. S. H. Nasr (1968), p. 31.

59. Quoted in R. V. Patvardhan (1920), vol. 1, p. clv.

60. S. H. Nasr (1978), p. 247.

See the entire book on Cista

LA LÉGENDE D'HIRAM

Articles les plus récents

LES SENTIERS D’HERMÈS